New Records Shed Light On Investigation that Led to Former Police Chief Diaz' Ouster

The newly released documents include interview transcripts from the investigation into whether Diaz created a job for and promoted a woman he was allegedly having an affair with.

By Erica C. Barnett

Newly released records from the investigation into former police chief Adrian Diaz and his former chief of staff, Jamie Tompkins, shed new light on efforts by Tompkins and Diaz to discredit SPD staffers who believed Diaz had hired, and created a new position, for Tompkins because they were having an affair. They also show that Diaz' security staff, who reported directly to Tompkins, were afraid of speaking out about the alleged affair because they believed they would be fired or criminally investigated if they talked.

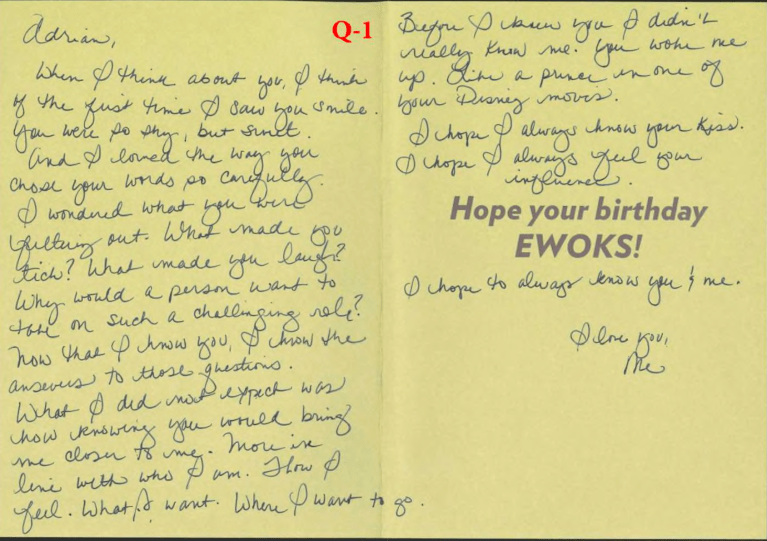

The records, which PubliCola received in response to a public disclosure request, include transcripts of interviews with Tompkins, Diaz, and three members of Diaz' security detail, along with a copy of a love letter written on an Ewok birthday card that investigators determined Tompkins wrote, based on an expert analysis of her handwriting.

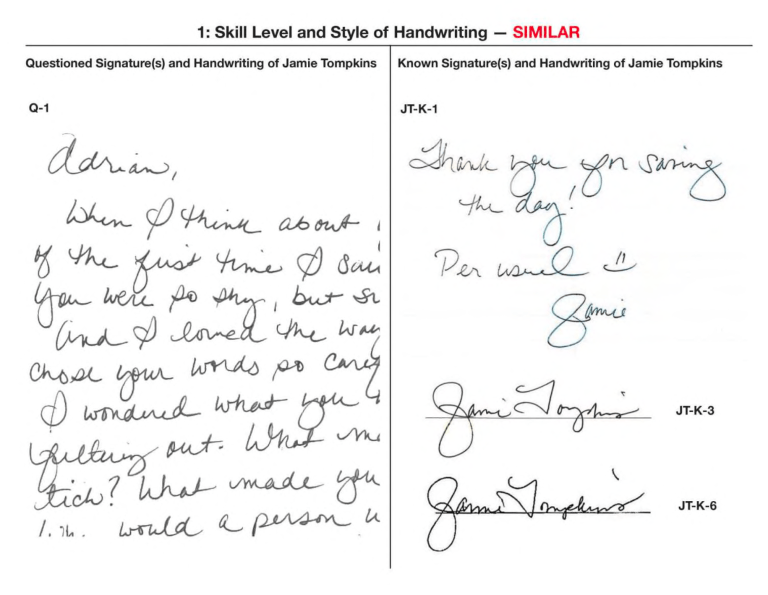

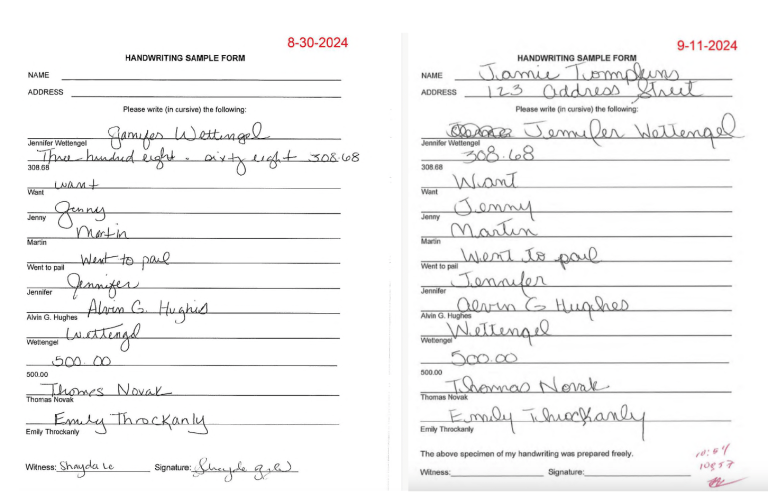

Outside investigators determined last year that both Tompkins and Diaz had lied to investigators about their relationship, and that Tompkins had falsified evidence in the investigation by disguising her handwriting in an effort to prove that she didn't write a love note to Diaz.

The investigation, by attorney Shayda Le from Barran Liebman LLP, was limited to "fact-finding" and came out after Tompkins resigned; she has since filed a $3 million claim against the city, alleging she was sexually harassed over the rumors about her and Diaz. Mayor Bruce Harrell demoted Diaz last May and fired him in December.

"It Scared the Crap Out of Me"

One of Diaz' security officers, Andre Sinn, found a (since much-discussed) apparent love note, written on an Ewok-themed birthday card, in the Toyota Highlander Diaz had been driving while waiting for a new Chevy Tahoe he had ordered to arrive. Sinn brought the card along to his interview and handed it over to investigators, saying he had held on to it for more than a year because he and the other members of Diaz' detail didn't know what to do with it and who they could trust. "To be honest, it scared the crap out of me," Sinn said.

Tay Gray-McVey, another member of Diaz' security team, said the team discuss "different ways to turn it in without getting in trouble for not turning it sooner." He assumed Diaz would fire them for telling anyone about the card; during the interview, a union representative, Matt Newsome, noted that Diaz kept a box in office that contained the badges of officers he'd fired, as if to say, "this is what could happen to you," Newsome said.

The handwriting analysis compared the writing on the card to two separate samples Tompkins submitted to investigators—one impromptu sample, a standard handwriting analysis worksheet, that Tompkins provided at the end of her interview, and another she submitted about two weeks later. The final sample looked noticeably different than other examples of Tompkins' writing, and caused the certified handwriting analyst to conclude that Tompkins had purposely disguised her handwriting so that investigators would be unable to conclude she'd written the card.

The handwriting expert, a certified document examiner, concluded that Tompkins wrote the love note and that her final writing sample "showed evidence of disguise."

Tompkins and Diaz have denied the allegations, and Diaz hired his own handwriting expert who he claimed had discredited the outside investigator's finding that Tompkins most likely wrote the love letter and later attempted to disguise her handwriting.

Special Treatment?

Many of the people interviewed during the investigation, including Sinn, said they didn't really care one way or another if Diaz and Tompkins were having an affair—that was between them. "But when you hire a person into that role and you ... bring them into our department, that, to me, is a huge problem, and then without divulging their relationship," Sinn told investigators.

Specifically, Diaz was accused of creating a new position—Chief of Staff—for Tompkins, then promoting her to his command staff and putting her in charge of Clancy as well as Diaz' own security detail. Then, SPD staffers claimed, he proceeded to give Tompkins special treatment, allowing her to work from home at a time when most people were expected to be in the office and spending large amounts of the work day "socializing," as Sinn put it, instead of actually doing work.

"I don’t think anyone really knows what her job is honestly," said Gray-McVey, who was interviewed when Tompkins still worked for SPD. "For a good portion, up until we got Chief [Sue] Rahr, we didn’t see her much in the office. Maybe one or two days for a couple hours."

Tompkins said in her interview that Diaz hired her for her expertise in journalism, attention to detail, and willingness to tell him the truth while others on his staff were content to be "yes men" telling him what he wanted to hear. "I'm a perfectionist and it needs to be executed in just the right way," he said.

Both Diaz and Tompkins claimed that the SPD chief had a chief of staff before Tompkins. For example, they said that Chris Fisher—SPD's chief data analyst, whose title was Director of Strategic Initiatives—was Diaz' previous chief of staff, even though he had a different title and responsibilities. "This isn't a new fancy position and it's not special," Tompkins said.

Investigators seemed unconvinced by this argument, noting that Diaz already had a different Director of Strategic Initiatives, Heather Marx, when Tompkins was hired. The Chief of Staff title has not been use since 2001, although various people has served as adjutants or aides to police chiefs since then.

Throughout her interview, Tompkins returned to the idea that people at SPD were inventing the controversy over her role, along with the alleged affair, because she looked and acted different than a typical SPD employee. Tompkins told investigators Diaz' executive assistant told her Gray-McVey "had a thing for me" and was "enamored" to the point of updating the Q13 FOX website constantly to see when her bio would come down (indicating she was about to start at SPD).

Diaz' assistant, Tompkins continued, "would get phone calls: 'What is she wearing today, where is she, is she going to be at this event?' And I asked her, like, 'Why—why would they want this?' and she’s like, "because they want to experience you. They want to have an experience with you. ... [because] you're from television."A communications training consultant once told her "they don't know what to do with you here," Tompkins told investigators. "She's like, 'People just stare at you, like... I can't possibly have a brain and really great ideas."

If Diaz did create a position for Tompkins because he was in a relationship with her, that would be a form of misconduct and potentially a misuse of city funds. Proving this kind of misconduct would require the city to demonstrate that the affair actually occurred.

Jamie Tompkins interview, August 2024

"Nervous and Scared"

Many of the most salacious details of Diaz' alleged comments about Tompkins have been reported before, including his alleged statement that he couldn't keep up with Tompkins sexually and told her to use her Rabbit vibrator when he wasn't around. But the interviews show that the stories Diaz' security detail told investigators were remarkably consistent and limited to information each man could have obtained firsthand—for example, in one instance when one person was driving and another was riding in the back with Diaz, investigators concluded that each story reflected what they could have heard from their relative positions in the car.

Brandon James, a member of Diaz' detail recalled Diaz telling him he couldn't have sex as often as Tompkins wanted, and said that he specifically suggested Cialis, not Viagra, as an effective male-enhancement pill. The two had initially bonded, James said, after he confided in Diaz about his own divorce and Diaz helped him get off the night shift so he could see his kids, James said. During one drive—around the time James took Diaz on a "road trip" to get a specially tailored suit—James said Diaz confided in him that he was considering a divorce from his wife because he and Tompkins "were dating and wanted to be together," and James advised him on how expensive and complicated divorce can be.

Around that time, both Gray-McVey and James said, they separately discussed various "cover stories" Diaz could use to explain why he was away from home so often, including the excuse that he was seeing a personal trainer. Diaz did later tell investigators he was seeing a personal trainer—Tompkins' brother—at her apartment building, meeting for their sessions in the conference room. James said he told Diaz he needed a more specific excuse that wasn't so easy to disprove. "I said, 'Quite frankly, you need to have better cover stories.'"

In her final investigation report, investigator Le concluded that Diaz and Tompkins most likely had had the affair and lied about it, based on testimony from the three security detail members as well as their obvious fear of retaliation by Diaz. "I noticed how nervous and scared all of the members of the security detail were to participate in the investigation," Le wrote.

"The members of the security detail described fear of retaliation from Mr. Diaz based on his historical behavior, explained that their trepidation came from the fact that their testimony would be easily identifiable and traceable back to them, and suggested that the investigation could seek other sources of information, such as phone records or vehicle data in order to reduce the pressure and potential backlash they expected to experience from providing truthful testimony that would be damaging to Mr. Diaz."

Additionally, Le wrote, there was no obvious reason why all three men would lie about Diaz. In an interview with investigators last October, Diaz suggested that Gray-McVey and James were both lying to help an unrelated officer who had sued the department, who Diaz said was "sleeping with" Gray-McVey. The interviewer seemed confused by this somewhat byzantine tale, and ultimately didn't find it germane, concluding that "Mr. Diaz made direct statements to Det. Gray-McVey and Lt. James about sexual and intimate interactions with Ms. Tompkins."

During her interview, Tompkins said there was "no way in hell" Diaz would have said he was having an affair with her, adding that the suggestion was "insulting" and "a form of sexual harassment."

"Paranoid"

Both Diaz and Tompkins claimed that people were surveilling them. Tompkins, as previously reported, believed officers from the West Precinct, which is directly adjacent to the her condo building, were hanging around her building to see if Diaz was going in and out. Tompkins had Diaz do "counter-surveillance" around her building, on one occasion watching a white SUV that she said had been "parked weird" and was "always facing my apartment"; she also put sensors on all her doors and "invested in all different types of security things."

Diaz, too, believed he was being surveilled and followed, and was worried his car and office might be bugged with listening devices. James recalled Diaz telling him he was sure he was being followed, and was "paranoid about believing his cars were being bugged." In an interview with investigators, Diaz said he believed people followed him home, and said "there were many times when I took in plenty of license plates because I thought I was being followed."

Although other SPD personnel, including Maxey, told Diaz that physical tracking devices are mostly a thing of the past—"if you want to get somebody, you don’t plant a bug anymore, yo can hack their phone. Just go directly to the microphone they’re already carrying around with them," Maxey told investigators—Diaz insisted on having his car swept for "bugs" and was alarmed when a sweeping device appeared to pick up something near one of the rear tires—most likely the Bluetooth system that monitors tire pressure on modern cars.

James said that, at Diaz' insistence, he searched his office for bugs, but told investigators it was really "just for show"—to demonstrate to Diaz that he had nothing to worry about. But Diaz continued to believe he was being followed and targeted. Often, he would stop in a parking lot and just sit there for "20, 30, 40 minutes," Sinn recalled, while his security escort waited for him to leave for home.

During those times, members of Diaz' detail believed he was on the phone with Tompkins. In an interview with investigators, Diaz denied calling Tompkins during those times, then said he talks to "hundreds of people" and finally conceded that it was possible she was among the people he talked to on the phone before going home.

Adrian Diaz followup interview, November 2024

"We Have This Bomb That's Going to Go Off"

Shortly after Mayor Bruce Harrell demoted Diaz in response to multiple sexual harassment complaints against him, Diaz came out as gay, telling people inside and outside the department that he had begun to question his sexuality a few years before making the announcement.

Both Gray-McVey and James told investigators it seemed clear that Diaz believed that if he came out as gay, it would be impossible for Harrell to fire him, because he would be a member of a protected class. Maxey said Diaz initially told him that "we have this bomb that's going to go off, it's going to reset all of this." After Diaz made this cryptic remark, Maxey recalled, he told Diaz that being gay didn't mean he couldn't have had an affair with Tompkins and created a position for her—the two things weren't mutually exclusive; sexuality is fluid.

At that point, Maxey said, Diaz "got very angry with me—he kept saying, you know, 'This means somebody would be betraying their true self and acting contrary to their feelings and their beliefs and what was right for them.'"

Diaz told investigators, and the public, that one reason he spent so much time hanging out with Tompkins was because she was one of his key emotional supports when he made the decision to come out as gay. However, investigators noted that in their lengthy interview with Tompkins, she never mentioned this among the many reasons she said she spent time with Diaz; nor did she mention personal training or working out, which were among the main reasons Diaz said he might have been seen entering and leaving her apartment building. Tompkins also told investigators she stopped "socializing" with Diaz outside of work once she started at SPD.

It's clear from the interviews with SPD staff that no one was bothered by Diaz' profession that he was gay; even the members of his detail who didn't believe him said it didn't matter to them if someone was gay or straight. This included OIG director Lisa Judge, who Diaz and Tompkins accused of "outing" him to other SPD staff before he announced his sexual orientation publicly.

Although Diaz and Tompkins both claimed Judge was telling people Diaz wasn't really gay, Maxey said the opposite was true—Judge told her she thought Diaz might have come out to her, and she wanted to know if she should offer him advice on coming out later in life, as a fellow member of the LGBTQ community "She was genuinely concerned that he was hurting," Maxey said. "You don’t have that level of concern if you’re doubting the reality of it."