Proposal to Allow Affordable Housing Near Stadiums Reignites a Familiar Debate Over Industrial Land

Can Seattle's maritime economy cooexist with new housing near the stadiums? And why does it feel like we've had this conversation before?

By Erica C. Barnett

City Council President Sara Nelson has reintroduced a proposal, shelved in 2023 to secure the Port of Seattle's support for an overhaul of the city's industrial zoning, that would allow up to 990 units of "industry-supportive housing" —half of them affordable to people making 90 percent or less of Seattle's median income—on two blocks of land just south of Lumen Field.

Although the city's original "preferred alternative" industrial lands policy included this housing, the final version adopted in 2023 excluded housing from the area.

While the Port has argued that allowing housing near industrial areas will permanently harm Seattle's maritime and industrial sectors, housing advocates point to an environmental impact statement done specifically for the industrial lands update that concluded housing is compatible with the kinds of businesses that are now allowed around the stadiums, like breweries, art spaces, and retail stores attached to clothing manufacturers.

In last week's meeting of Nelson's governance and accountability committee, representatives from the Port and maritime unions squared off against affordable housing advocates (the Housing Development Consortium), neighborhood business groups (the Alliance for Pioneer Square), and the Seattle Building and Construction Trades Council, which argued the zoning change would bring thousands of new jobs to the area.

Port Commissioner Fred Felleman said the Port had agreed to allow hotels around the stadiums, but "long-term housing in industrial zone without basic amenities is unacceptable and compromises our ability to attract new tenants. Please don't put housing in conflict with job growth."

Former Redmond mayor John Marchione, who now heads up the Washington State Public Stadium Authority, countered that the zoning change would create a "new, fully formed community with "jobs, housing, transportation and entertainment." The area is less than a mile from two light rail stations, which currently have the lowest and third-lowest ridership of the 19 stations on Sound Transit's north-south 1 Line—largely because almost no one lives near them.

Panel members told the council they agreed to put off the housing question until a later date in order to ensure that the industrial lands policy—which had been in the works for years—would pass with the backing of the Port, which had threatened to withhold support for the plan if it allowed housing near the stadiums. The new policy barred housing in a small area called the Stadium Overlay District, which includes two blocks just south of T-Mobile Field and a long, skinny strip of land next to Terminal 46, known as the WOSCA site for its former owner, WOSCA Terminals.

As part of the 2023 deal, Washington State Public Stadium Authority consultant Lizanne Lyons told the council, Mayor Bruce Harrell's office told the housing advocates to come back in the future to seek zoning change to allow housing in the two blocks south of the stadiums. (The WSPSA owns Lumen Field.)

"It was frankly at the 11th hour that we were informed that the deal we thought we had, that we had been told we had, [to allow up to] 990 units of housing in the stadium district were taken out," Lyons said. "We were told that the timing was sensitive ... 'Come back in a year and get the zoning change you need to enact the housing that we have repeatedly told you you could have.'"

The Port and longshore union argue that allowing apartments in the area would create traffic bottlenecks for trucks and make it impossible for Terminal 46—which currently serves as storage space for imported cars—to be used for container shipping in the future. Before the council can take up any proposal to allow housing near the stadiums, Councilmember Dan Strauss said, they must first make sure they know how that terminal will be used in the future, what kind of development will take place at the WOSCA site (a decision that won't happen until after the World Cup games next year), and how any new housing will impact freight traffic in the future.

"There are other ports to the north and south that could just as easily take this traffic, and it would be a shame if they start taking our cargo because I- 90, that connects Seattle to the heartland of America, into Boston, can't get through that last half-mile at the end to meet the port," Struass said.

The city's final Environmental Impact Statement concluded that while housing growth can increase car traffic, it could also lead to better infrastructure for transit, pedestrians, and cyclists in "areas with histories of long-term underinvestment" like SoDo. The FEIS did also found that there would be no "significant adverse environmental impacts" from adding 990 new housing units in the area.

As Mike Merritt, a former senior executive policy advisor at the Port of Seattle, recently wrote in Post Alley, low shipping volumes—not traffic on and around I-90—have led to slowdowns and closures at several Seattle terminals, including Terminal 46, which has not had container service since 2019.

Housing opponents have also argued that the city has failed to consider the potential impacts of natural disasters or an emergency that requires the military to access Seattle by sea.

Channeling these arguments, Kettle said the city had failed to consider the possibility of several types of potential disaster on people living in the area. "There's not been any talking about Love Canal-type considerations for this location," Kettle said. Moreover, "SODO is between two fault lines [and sustained] great damage from earlier earthquakes, like in 2001 ... These considerations have not been talked about— liquefaction zones, tsunami, in terms of the elevation, the inundation of the water. ... We look at the LA fires right now, we look at the hurricanes in the Gulf, in Florida. These are major considerations."

Instead of standing for "Final Environmental Impact Statement," Kettle quipped, FEIS should have stood for "Flawed Environmental Impact Statement" because "it didn't really address some of the unique circumstances" in the two-block area.

In fact, the EIS did consider geological hazards, traffic impacts, and the other potential issues Kettle and Strauss identified. In a section about geologic hazards, the EIS notes that "modern building codes" are designed to mitigate against risks associated with earthquakes in historically industrial areas across the city, including in existing residential neighborhoods like Pioneer Square, Ballard, and Georgetown.

"With mitigation, all these impacts together would not be considered significant," the EIS concluded. If the Big One hits, of course, it won't really matter if you live near the stadiums or elsewhere in the city; all of Seattle, but especially areas near waterfronts, will face catastrophic destruction.

Panel member Monty Anderson, head of the Seattle Building & Construction Trades Council, said he was familiar with all the arguments against housing near the stadiums—particularly the ones about future uses for the WOSCA site and Terminal 46. "'What if the Coast Guard comes? What if they build an arena? What if we get offshore wind?'" Anderson said. "Everybody knows that it's just delay."

Lyons, from the stadium authority, noted that it's been decades since the two blocks south of Lumen Field have been used for industrial purposes. "It's a lot of vacant buildings and deteriorating warehouses and vacant lots," she said, plus "some good development on First Avenue South."

Apparently responding to public commenters who argued that having more street-level activity would improve public in the area, Kettle said that wasn't true—just look at downtown, Belltown, and the Chinatown-International District, which have lots of people but also lots of crime. "If residence was the determining factor of public safety, those should be the three safest places in the city. But they're not." Legislation the council passed last year, including surveillance cameras, higher pay for police, and "stay out" zones for people who use drugs in public, create "the conditions for safety," Kettle said; "housing itself will not."

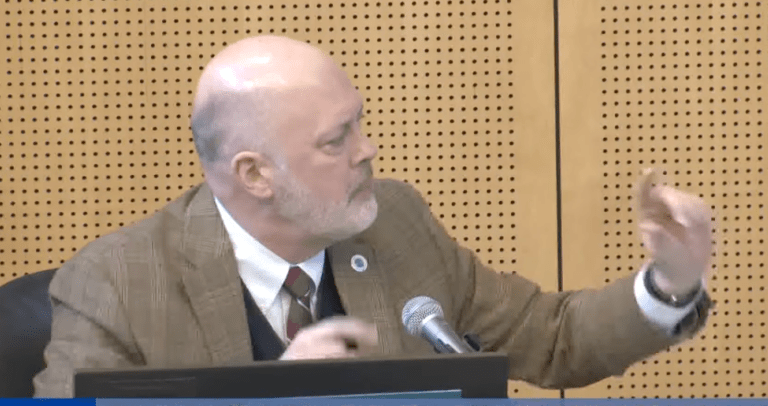

Later in the meeting, Kettle lost his temper at Anderson after the union leader commented that some people had been "fed lines" and "talking points" by opponents of the housing proposal. "We all do that," he said. Although the remark seemed to be aimed at the longshoremen who testified earlier, Kettle seemed to take it as a personal attack.

Cutting Anderson off, Kettle said his views on industrial land policy are based on his "service as a naval officer, an international security expert [who] understands international trade," as well as his "studies," "academic experience," and time on the Queen Anne Community Council. "I'm not being a mouthpiece for anybody that's out here, and I just want to make that point clear," Kettle said.

That prompted this dramatic exchange, in which Anderson accused Kettle of talking to him like "a stupid Mexican construction worker" and Kettle shouted Anderson down:

After the meeting settled down, Kettle said he "respect[ed]" Anderson, but did not apologize for his outburst.

Nelson's committee will take up the legislation again in February.